What Are All These Ingredients In My Pre-Workout?

If you have been in the fitness space at all in the last 50 years, chances are you have been intrigued by the supplement industry and all these cool ingredients and formulations that are sold with promises of supercharging your results. In more recent years, consumers have been increasingly more well-informed, leading to a demand for only the most scientifically validated ingredients to be included in sport supplements. While this has been mostly a positive improvement over the supplement industry of 20 years ago, the current state of the industry is such that a single PubMed link showing the benefits of a supplement is enough for companies to slap on ad copy such as “clinically dosed” or “scientifically proven” onto their labels. Many companies even go as far as posting the supporting research on their websites for you to see for yourself! This has led to supplement formulations with dozens of active ingredients, each of which has been supposedly rigorously tested through scientific examination.

By the tone of my writing, you can probably tell that I am not going to be in agreement with the strength of most of these claims. There are only a handful of supplements that truly have large amounts of data supporting their use for sport performance, but in this article I will be covering supplements that fall in the other camp, where the claims drastically overstate the evidence. I am restricting my discussion today to non-dietary supplements (i.e. not protein powder, multivitamins, etc.). The ingredients we discuss here are going to be the ones that you find in many “pre-workout” formulations, and we will go through each of them so that you can more accurately make informed decisions as to whether you want to pay money for them.

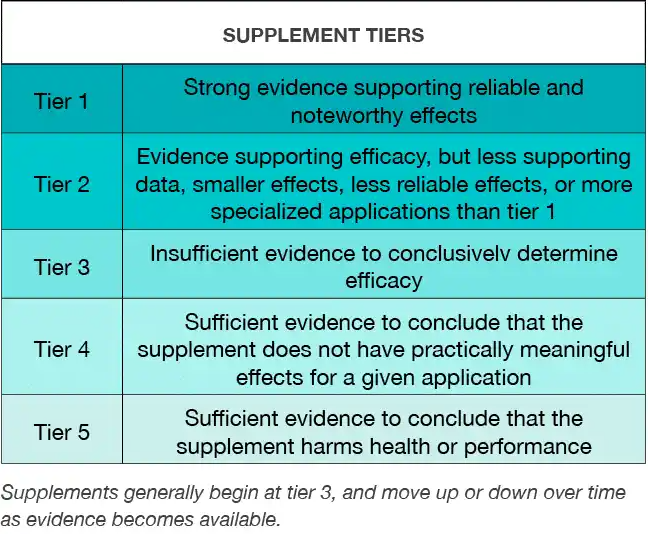

Before we do that, I want to introduce the concept of the supplement tiering system. This tiering system gives us a useful measuring tool for categorizing supplements into neat categories based on the amount of scientific support they have.

The idea with this system is that it gives us a way to rank supplement ingredients, so that if the decision to supplement is made, we can have a good idea on which ones to start with. It’s important to note here that the tier system should be specific to a given application. For example, a supplement might be tier 3 for endurance performance, but tier 1 or 2 for strength. For our purposes, I will assume that the reader is interested in things that are purported to increase performance in things like muscular strength, muscular power, muscular endurance, and anaerobic capacity. There are a handful of supplements that I would consider tier 1 in this context (creatine, caffeine, beta-alanine), and I will cover that in a separate article. Today, I am going to talk about the supplements that fall in tiers 2-5 but are still extremely common in pre-workout supplement formulations.

Throughout this article, I will break down each supplement ingredient and explain three aspects on each one:

Proposed Benefits: This is what you usually see on your supplement label. Things like “Increased strength” or “supports fat loss” and other claims along those lines.

Proposed Mechanisms: These are the things that sound more sciencey and that supplement companies like to put on their website under sections like “how does it work”. Usually there is a brief description of whatever pathway it is purported to affect and how that affects the performance outcome of interest.

The Evidence: This is the important part. This is where we talk about what research has found in regard to the mechanisms, benefits, and their effect on performance, and what we can actually confidently take away from that research. A common theme that we are going to encounter on this journey today is that there is often pretty good evidence that a given supplement affects whatever mechanisms it claims to affect, but the translation from that mechanism to performance is lacking.

Tier Rating: After evaluating all the above, we will place each ingredient into a tier based on the current state of the evidence.

When we are evaluating evidence, we want to be looking for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (combining all the studies on a topic into one big analysis) to really come to a confident conclusion as to whether something works or not. Individual studies, especially in this field of research, often have very small sample sizes, which can give us false positives or negatives based on how the study is designed. Some of the ingredients we are covering today do not have enough studies completed on them to even warrant an effective meta-analysis, so we will do our best with what is available.

The supplements we will be covering here are:

Proposed Benefits

Increased blood flow

Increased energy

Improved strength, aerobic performance, muscle endurance

Proposed Mechanisms

The main mechanism of potential performance improvement from citrulline supplementation is in citrulline’s role as a nitric oxide precursor. Once it is absorbed, it gets converted to arginine, which in turn gets converted to nitric oxide. Nitric oxide acts as a vasodilator, which increases blood flow to the active muscles. There is also some evidence that citrulline may aid in clearing ammonia, while malate may reduce the rate at which acidic by-products accumulate in the muscle. Mechanisms are cool, but how does all this translate to actual performance?

The Evidence

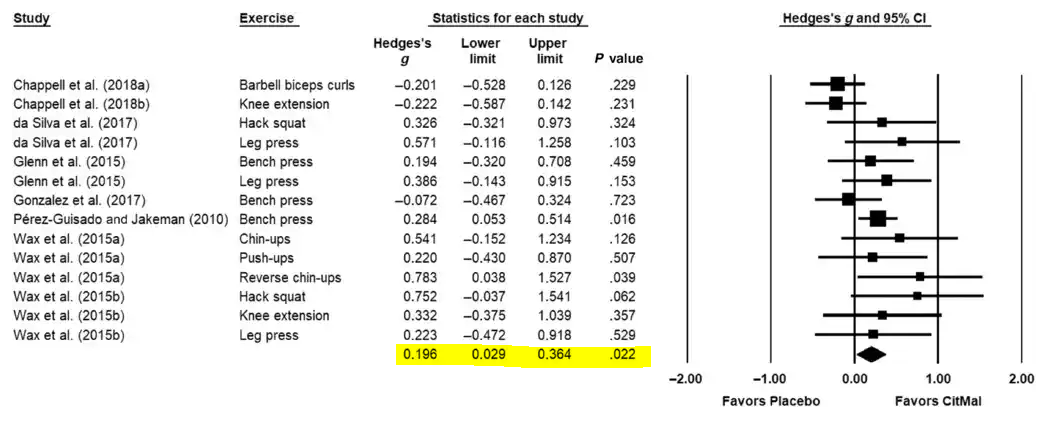

Out of the ingredients we cover today, this has the most promise. Citrulline has some support for acutely benefitting measures of strength endurance (reps to fatigue) as covered in this meta-analysis of 8 studies. A strength of the studies included in this meta-analysis, is that they used performance measures that are actually relevant to lifters (leg press, pushups, bench press, etc.). Here is the funnel plot of all the studies included:

Another reason I wanted to include the image of this funnel plot is that it highlights the importance of using meta-analyses to come to more confident conclusions, especially in this field where sample sizes are so small. If you look at each individual study, almost none of them reached statistical significance on their own (p < .05). So if you were trying to piece together the literature on this topic without a meta-analysis, you might be tempted to think that citrulline malate is dead in the water, almost none of the studies find a significant effect! But when we put them all together, an overall effect (highlighted) starts to shine through.

There also seems to be a similar level of support for citrulline’s role in increasing strength and power outcomes, as seen in this meta-analysis of 12 studies. Similar story here, with most individual studies finding no benefit but a small effect shining through when studies were combined.

These two meta-analyses show some promise, but the effects we see are BARELY crossing statistical significance and having 8 and 12 studies in a meta-analysis is not super compelling. It is possible that with more research that effect size becomes more solidified (hopefully away from the zero line).

To temper excitement even more, something you need to remember about supplement research is that we are almost always evaluating specific ingredients in isolation, but when we consume them in something like a pre-workout that has several ingredients, we can’t just assume that the benefits of all the ingredients can just be stacked up for one combined mega-effect. I think this is what has happened with Citrulline’s inclusion in most pre-workout formulations.

When you have a pre-workout supplement that contains caffeine, which provides similar acute benefits as citrulline on strength endurance and power, it is not really clear if those effects are actually additive. This study (small but the only one to my knowledge that looked at this) tested this by comparing several performance measures under the following conditions: caffeine (5mg/kg), citrulline malate (12g, with a 2:1 citrulline-to-malate ratio), a combination of both (caffeine + citrulline malate), or a placebo. This is the sort of design we need to see if citrulline provides a benefit above and beyond what caffeine already gives you. It is worth noting that this dose of citrulline malate is MUCH higher than what you see in most pre-workout formulations, so if there is an effect of citrulline malate we would expect to see it here.

What they found was that there was no extra benefit of caffeine + citrulline over caffeine alone in any of the measures. Now, I am not saying that there is not a possible additive effect of citrulline, but the research just isn’t there yet, and we are getting a lion’s share of the benefit we are after from caffeine alone. Caffeine also has the added benefit of increasing 1RM performance and other shorter duration performance tests, which citrulline does not. As a side note, citrulline malate is one of the pricier ingredients in most formulations, much more than things like caffeine or beta-alanine. So is it worth paying extra money for this potential very small advantage of citrulline + caffeine over caffeine alone in strength endurance tasks? Maybe for you it is. One situation where I could see citrulline being a defensible inclusion in a supplement is in a stim-free pre-workout.

Tier Rating- 2

Proposed Benefits

- Enhance fat loss

- Enhance power output

- Enhance endurance capacity

Proposed Mechanisms

Betaine (Trimethylglycine) is a dietary supplement derived from beets, and serves as an active metabolite of the vitamin choline. Betaine can be produced by the liver and kidneys from the oxidation of choline, but also can be obtained exogenously through foods such as wheat bran, wheat germ, spinach, beets, wheat bread, and shellfish. There are two effects relevant to us that Betaine is claimed to exert:

Strength and Power- When it comes to enhancing strength and power, there are three main mechanisms that are thought to be at play. The first is by betaine’s proposed ability to increase creatine biosynthesis by providing a methyl group to guanidinoacetate. The second is in regulating cellular hydration, it is thought that betaine may restore osmotic balance and alloy the cytoplasm to retain water, which would be useful during periods of osmotic stress, such as exercise.

Body Composition- Betaine is thought to exert an effect on fat loss through the influencing of various enzymes and pathways associated with fat metabolism, promoting fat breakdown and inhibiting fat storage. Additionally, it is thought that betaine might have effects on growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) levels, which may promote protein synthesis.

The Evidence

Strength/power- The research is pretty limited here, but there is one systematic review from 2017 that we can take a look at. A whopping 7 studies met the eligibility criteria for this systematic review. For reference, some of the more evidence-based supplements such as caffeine, creatine, and beta-alanine typically have 40+ studies to pull from when conducting systematic reviews and meta-analyses. But let’s press on. The studies included here ranged in duration from 1 to 6 weeks and all of them used a dose of 2.5g, which is what you will typically see in supplement formulas. Of the seven studies, only four of them measured both strength and power, with one measuring only strength, and the remaining two measuring only power. To further complicate things, the way that each study measured strength and/or power varied considerably across the 7 studies, which presents an added layer of difficulty when we try to analyze them together.

When it comes to assessing strength in research in a way that is practically applicable to the real-world, we usually want to see some sort of 1RM testing. However, only two of the included studies did this, with the others using isokinetic dynamometer or transducer devices. To measure power, the included studies used vertical jump tests, bench press throw, and power output during bench press and back squats.

There was no meta-analysis component of this study, meaning the authors did not try to statistically combine the effects of the studies to derive an overall effect. This is likely due to how varied the outcome measures were among the studies, but this means the best we can do is look at how each of the studies fared individually. Of the 7 studies, only two reported any significant improvements in strength or power.

Based on the lack of clear and consistent results, and variation in study quality/design/outcome measures, this is just not a field of research that we can draw any confident conclusions from at this time.

There is one other individual study that bears mentioning due to the amount of times I see supplement companies citing it as support for the effectiveness of betaine, and that is this one from 2022.

This study looked at 10 handball players and investigated the effects of 2-week betaine supplementation on testosterone, and lower and upper body muscle endurance as assessed by leg press and bench press repetitions to fatigue, respectively. Betaine supplementation resulted in greater leg press repetitions (Betaine: 35.8 ± 4.3; Placebo: 24.8 ± 3.6, Cohen’s d = 2.77), bench press repetitions (Betaine: 36.3 ± 2.6; Placebo: 26.1 ± 3.5, Cohen’s d = 3.34) and higher total testosterone (Betaine: 15.2 ± 2.2; Placebo: 8.7 ± 1.7 ng.mL−1, p < 0.001).

Those are some pretty impressive results from just two weeks of supplementation. Some, including myself, might say suspiciously impressive. To give you a frame of reference, typical Cohen’s d (a measure of effect size) values for creatine for increasing lean mass and other strength-related outcomes usually fall somewhere between 0.3-0.6. So to see an effect size of about 10 times that for a two-week supplementation protocol is very surprising. I don’t think you would even get these sorts of results from two-weeks of heavy duty anabolics.

Speaking of anabolics, the testosterone increases seen in this study are equally interesting. The increases we see in this study are roughly equivalent to what we would expect after injecting 240-245mg of straight up exogenous testosterone per week.

All of these findings are so far outside of what we see in the rest of the betaine research as seen in the 2017 meta-analysis we discussed above, that they are hard to take at face value. I am in no way accusing the authors of this paper of any sort of fraudulent activity, but unless you are willing to believe that betaine is as effective as literal anabolic steroids, I don’t think we can put much stock into these findings.

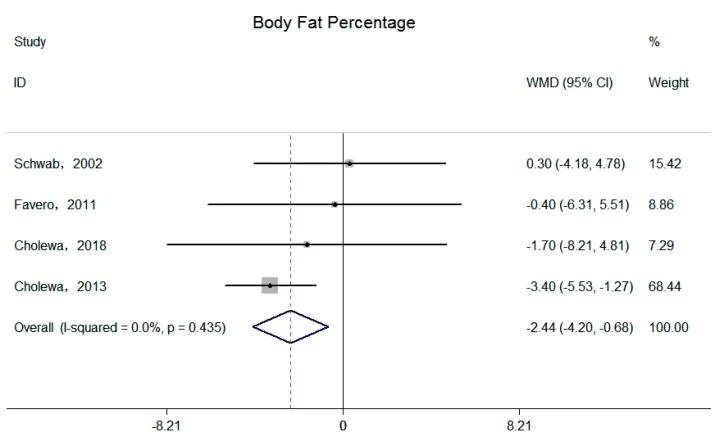

Body Fat- The most recent meta-analysis looking at this claim is this one from 2019. This meta-analysis included only 6 studies, and all six of them employed a parallel group study design, meaning that they had separate placebo and experimental groups, but there was no crossover element (where every participant did both conditions) which reduces the strength of the conclusions we can draw here. Of the six studies included, only four of them measured body fat mass directly, while the other two measured BMI or overall weight change which is not great if we are interested specifically in body fat changes. When we isolate those four studies that specifically measure body fat, there indeed was a statistically significant effect of betaine on body fat loss. However, two of the studies were by the same research group and those two studies combined to make up for 75% of the statistical weight of this analysis.

There is nothing wrong with that, necessarily, but when we are looking to make confident conclusions about the efficacy of a supplement, this body of research is still way too early to do that.

Tier Rating- 3

Proposed Benefits

Decreased protein breakdown and enhanced protein synthesis

Increased cholesterol synthesis

Enhance testosterone response, decrease cortisol response to exercise

Proposed Mechanisms

HMB is a metabolite of the essential amino acid, leucine. Supplementation has been suggested to accelerate muscle recovery following high-intensity exercise by reducing markers of muscle damage and stimulating muscle protein synthesis through an up-regulation of the mammalian/mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1, a signaling cascade involved in coordination of translation initiation of muscle protein synthesis.

The Evidence

Let’s first talk about the possible hormonal responses to HMB supplementation. This 2022 meta-analysis of 7 studies looked at the effect of HMB supplementation on cortisol and testosterone responses to exercise. The main analysis found no effect on either outcome, however, subgroup analyses found a significant effect on post-exercise testosterone in activities that had combined anaerobic and aerobic components to them. Pretty cool huh?

Not so fast. While technically this was a statistically significant result (barely, at p=.039), the mean difference in testosterone concentration was only 1.60 nmol/L. For reference, anywhere between ~11 to 35nmol/L is considered within a normal range. Given that the normal intraindividual variation in serum testosterone (difference within the same person at different time points) is larger than this supposed increase, it is hard to ascribe even this small testosterone increase to HMB supplementation. Even if we took this small increase in testosterone at face value, the degree of testosterone change that is necessary to observe even small strength improvements is MUCH larger. This is a perfect example of how something can be statistically significant without being practically meaningful.

To further this point, let’s cut out the middle man (testosterone increases) and let’s now look at those performance outcomes and see what happens. Before we get to the meta-analyses there are on this question, I want to talk about one of the individual studies I see floating around that are commonly used to support HMB use, just to give you an idea of the types of issues we have in this line of research. This 9-week study on 22 resistance trained males concluded that HMB supplementation increased lower body strength and provided favorable body composition changes. I have a few issues with that conclusion. First, they used skinfold and single frequency BIA to measure body composition, which is likely not precise enough to reliably capture the small changes in body composition we would expect here. Second, this was a parallel group design, meaning there was a control group and intervention group but each subject only completed one of the conditions. This limits the strength of the study because we cannot rule out that one set of subjects just happened to be a little bit more responsive to the resistance training program, independent of any effect of HMB.

Lastly, and most importantly, the authors chose to use a 90% confidence interval in their statistical analysis, which is not against the law or anything, but it just is not common in this field of research. Using a 90% confidence interval versus the more common 95% confidence interval allows for smaller or less reliable differences between groups to register as “significant”. Combine this decision with the fact that the one significant strength finding (leg extension) was barely statistically significant (p = .05), things start to get a bit more fishy, because if they had used the standard 95% confidence interval, they almost certainly would not have had a significant finding. Overall, this study does not provide strong support to the claims.

Let’s move on to the meta-analyses.

There are two meta-analyses on HMB that I am aware of. The first one, which included 9 studies, concluded that all strength and body composition outcomes were insignificant, especially in trained lifters.

The second meta-analysis looked at measures of post-exercise muscle damage, acute immune and endocrine responses, and muscle mass/strength outcomes. Overall, there was a slightly favorable effect on some markers of intramuscular anabolic signaling, muscle protein synthesis, and muscle protein breakdown. However, we have to be really careful when looking at these acute responses and extrapolating to the long-term training outcomes we care about. Just because something improves the muscle synthetic response right after training, doesn’t mean it will have an effect on long-term training outcomes (see BCAAs). So all in all, these findings don’t really get me excited.

Lastly, you may remember earlier that I mentioned that HMB is a metabolite of leucine, and may be thinking to yourself, well why would this be any better than just a normal complete protein supplement? And you would be absolutely right. This is one of the key weaknesses with this line of research, very few of the studies use a protein-matched control group which means that any of the effects we are seeing, particularly with protein turnover, could simply be from having a bit more protein. Since protein turnover is a key mechanism of it’s supposed effect, it is likely that whatever effect is present diminishes even further with adequate dietary protein intake.

Tier Rating: 4

Proposed Benefits

Stress relief

Improve cognitive performance

Proposed Mechanisms

It is hypothesized that during exercise, an increase in the ratio of serotonin-to-dopamine may be one of the factors that induce central nervous system fatigue. Tyrosine is the amino acid precursor to dopamine, and so it is thought that elevating blood levels of tyrosine would result in a smaller serotonin-to-dopamine ratio since tyrosine and tryptophan (precursor for serotonin) compete for transport across the blood-brain barrier via the same carrier mechanism.

The Evidence

This meta-analysis of 8 studies found no effect of tyrosine supplementation on endurance performance, measured via time to exhaustion tests or time trial performance.

To my knowledge there is no systematic review or meta-analysis looking at the effect of tyrosine on strength outcomes. The only study I could find that even attempted to look at this was this one, which found no effect on various measures of muscular strength and muscular endurance.

What about cognition? Here the research is a little bit more promising. This systematic review paper on 15 studies found that tyrosine supplementation improved some measures of cognitive performance, with greater effects in conditions where mental strain was increased (sleep deprivation, stressful situations, etc.).

While most pre-workouts that include tyrosine do so because of the cognitive effects, it stands to reason that we would be interested in cognitive effects that improve performance. So if tyrosine seems to enhance cognitive performance, especially in situations where stress is high, why would that not translate to better performance? One limitation to the above research is that the performance tests do not really require a ton of cognitive effort. Usually we are looking at things like a time to exhaustion trial, a specific exercise for reps, 1RM, etc. However, maybe we would see a performance effect in a physical test that requires a skill component as well (i.e. Olympic lifting, team sports that require strategic decisions, etc.). Those things just happen to be more difficult to objectively assess.

Another potential confounder in this research is the lack of control for dietary protein intake. Since tyrosine is an amino acid, it is found in most protein-containing foods. The studies on cognitive performance rarely, if ever, control for habitual protein intake. I would assume that subjects with lower dietary protein intake would seem to benefit more from a tyrosine supplementation due to having lower levels to begin with, but could they achieve the same benefit from simply increasing their overall protein intake? Lastly, for our purposes here as we evaluate common pre-workout formulations, if we are already ingesting caffeine are the cognitive effects of tyrosine additive to the established cognitive benefits of caffeine? Ideally we would like to see some studies comparing three groups: A placebo, caffeine only, tyrosine only, caffeine + tyrosine. That would give us a clear picture as to how much of the effect of tyrosine is additive when a formulation includes both caffeine and tyrosine.

Unfortunately, the research is not in a place to really answer these questions.

Tier Rating: low 2 or high 3 for cognitive benefits, 3 for physical performance outcomes

Proposed Benefits

Increased endurance performance

Enhanced recovery

Enhanced focus

Proposed Mechanisms

Taurine is a sulfur-containing amino acid that is derived from the metabolism of another amino acid, cysteine. It is abundant in skeletal muscle and can be found in dietary sources such as animal proteins. It plays a role in various metabolic and physiological processes such as glucose and lipid regulation, energy metabolism, anti-inflammatory modulation, and antioxidant actions. Due to having wide-reaching effects, taurine has been proposed as an ergogenic aid in almost every type of exercise.

The Evidence

This 2021 systematic review looked at the effects of taurine in various performance outcomes including VO2 max / time to exhaustion (n = 5 articles), 3 or 4km time trials (n = 2 articles), anaerobic performance(n = 7 articles), muscle damage(n = 3 articles), peak power (n = 2 articles), and recovery (n = 1 article). So while a total of 19 studies were included, which is pretty decent as far as supplement research goes, each individual performance outcome had seven or less studies which limits how confident we can be in any conclusions, especially if the effects are not extremely consistent. Training status across the studies ranged from untrained subjects to well-trained endurance athletes, and taurine dosages ranged from 0.5g to 10g. Both of these factors make it even more difficult to come to an overall conclusion.

Going through every individual study mentioned in that review is not really in the spirit of making overall conclusions that I am trying to accomplish with this article, but it is there if you want to read it. Essentially, for each of the performance outcomes there tended to be meaningful impacts to some biomarkers of interest (blood lactate, muscle damage, soreness, fat oxidation, creatine kinase, etc.) but effects on actual performance were inconsistent or negligible. The most promising effects were seen in measures of endurance performance (time to exhaustion and time trial tests). This is to be expected of a supplement in it’s infancy, even ones that turn out to have small positive effects, as it takes a while for the research to accumulate enough statistical power to get a firm idea of what’s happening.

As far as potential cognitive benefits go, most of the research I could find were in subjects dealing with brain injury or other types of brain dysfunction, which you simply cannot generalize to a healthy population. I only included these as I often see supplement companies using these as “evidence”.

If anything, there is some evidence that including taurine in a multi-ingredient beverage that includes caffeine actually DECREASES the beneficial cognitive effects of caffeine (here, and here). I am not saying this is definitely the case, but what little research is available on the cognitive effects in healthy people is not promising.

Tier Rating: 3

Conclusion

We covered a good amount of supplement ingredients today, and looked at them individually to assess their merit. However, it is important to understand that even when we talk about supplements that do seem to be effective, just tossing them all into one formula does necessarily mean that their effects will stack on top of each other.

Written by: Chris Bonilla, Black Iron Training & Performance Nutrition Coach